One day you reach for a cup. Something catches. It passes. Then it returns—lifting, dressing, even sleeping. The pain localizes high in the arm. It deepens. It lingers. The shoulder stiffens, subtly. This isn’t weakness. It’s something structural. And it doesn’t leave on its own.

Tears aren’t always dramatic—they often develop slowly and silently over time

Full-thickness tears get attention. But partial tears wear silently. Repetition, age, posture—all contribute. Athletes tear with one swing. Older adults tear with time. The tendon thins, frays, retracts. You don’t hear it snap. You just stop trusting your arm one day.

Imaging confirms what the exam already suspects, but it doesn’t always tell the whole story

X-rays check alignment. MRIs reveal the tear. Ultrasounds offer dynamic views. But not all tears hurt. And not all pain reflects visible damage. A small tear may disable. A large tear might go unnoticed. Doctors balance the scan with your story. The image isn’t the diagnosis—it’s a piece.

Not every tear requires surgery, but delay can limit future repair options

Some tears respond to rest, therapy, injections. But others progress. The longer the delay, the harder the fix. Retracted tendons shorten. Muscles atrophy. Bone spurs form. Scar tissue settles in. Time narrows options. That’s why monitoring matters—even when pain fades briefly.

The decision to operate considers age, activity, tear type, and tissue quality

A young athlete with a full tear? Likely surgery. An older adult with a partial one? Maybe not. Surgeons assess tendon mobility, muscle condition, and patient goals. Function guides choice. Not just pain. Not just tear size. Repair is never one-size-fits-all.

Arthroscopic surgery has replaced open techniques in most cases, but both still exist

Most rotator cuff repairs happen with a scope. Small tools, small incisions, camera guidance. But some cases require open access. Scarred tissue. Multiple tears. Revision surgeries. The method depends on access, not preference. You don’t choose the approach—the tear chooses for you.

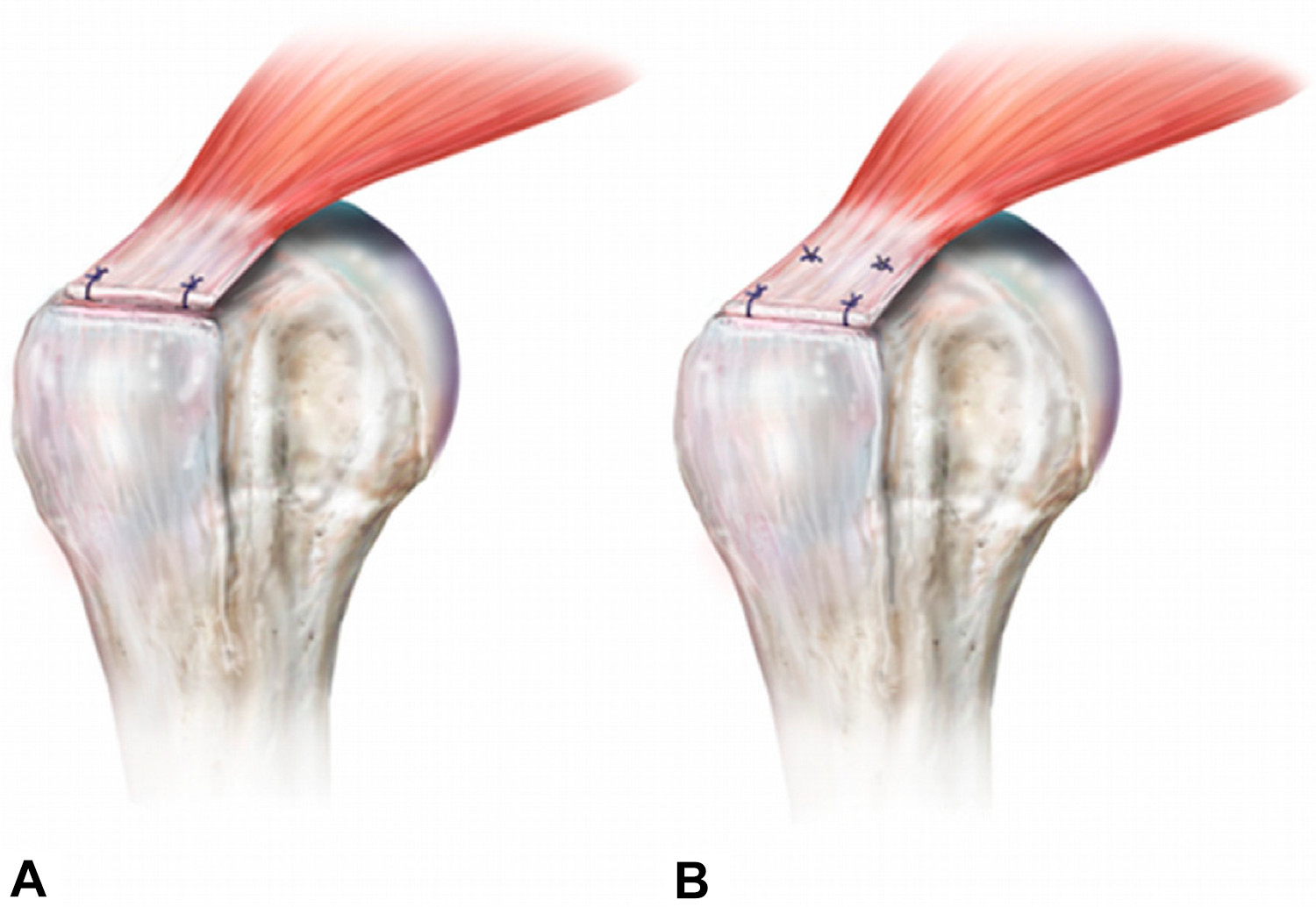

Anchor placement secures tendon to bone, but healing depends on biology, not just hardware

Surgeons place sutures. Threads pass through tendon. Anchors embed into bone. But healing doesn’t come from stitches. It comes from your body’s response. Tendon must reattach. Bone must accept it. That’s slow. That’s unpredictable. You leave with hope, not guarantee.

The first few weeks after surgery feel more like waiting than healing

You wear a sling. You sleep upright. You avoid movement. The arm feels useless. But this immobility protects the repair. The tendon rests against bone. Scar tissue forms. Activity too soon disrupts that process. Patience isn’t optional. It’s mandatory healing time.

Physical therapy begins cautiously and progresses slowly over months

Phase one: passive motion. Someone else moves the arm. Phase two: active assist. Then active. Then resistance. Each stage takes weeks. The therapist watches angles, pain, compensation. One wrong motion sets back progress. Progress is fragile. Rebuilding takes discipline more than strength.

The shoulder regains movement first—strength returns last, if it returns at all

Flexibility improves. You lift higher. Reach easier. But lifting weight lags behind. Strength comes in months. Maybe a year. Sometimes not fully. Rotator cuffs heal stiff before strong. The tendon repairs before the muscle does. That delay frustrates—but it’s expected.

Complications include stiffness, re-tear, and chronic pain even after a textbook surgery

Not every result is perfect. Some shoulders freeze. Some tears recur. Some pain remains. These outcomes don’t reflect surgical failure. They reflect healing complexity. Tendons differ. Bodies vary. Recovery isn’t guaranteed. Expectations must match reality—or disappointment becomes part of healing.

You can function without a fully intact rotator cuff, but mechanics change forever

Some people regain full use. Others adapt. They learn new movement patterns. They avoid overhead lifts. They rotate differently. The shoulder compromises. You do too. Surgery restores structure. It can’t always restore normal. Success is often measured in sleep, not pushups.

Age doesn’t disqualify you, but it redefines what recovery might look like

Elderly patients can still have surgery. But the goals change. Less about full strength. More about dressing independently. Less about throwing. More about sleeping. Healing slows with age. So does tendon quality. Surgeons weigh benefit against burden. Not all tears get chased.

Some patients feel better before full healing, which tempts them to do too much too soon

The pain fades. You ditch the sling. You reach too far. That’s when re-tears happen. The tendon isn’t ready. Pain is not the guide—biology is. Surgeons warn this often. Still, many return to activity early. And often, they return to the OR next.

The truth about rotator cuff repair is that it treats the structure—not always the function

Surgery closes a tear. It reattaches tissue. But motion, strength, and comfort require more. They require time, therapy, adaptation. Surgery starts the process—it doesn’t complete it. That difference separates satisfied patients from frustrated ones.

Source: Best Orthopedic Surgeon in Dubai / Best Orthopedic Surgeon in Abu Dhabi