The emergence of a bone tumor, whether detected incidentally on an X-ray or signaled by persistent, unyielding pain, immediately elevates a seemingly straightforward musculoskeletal issue into a critical diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. This moment often necessitates a rapid shift from general orthopedic care to the highly specialized field of Orthopedic Oncology. Unlike a routine fracture or joint replacement, the presence of a tumor—be it benign, malignant (primary bone cancer), or metastatic (cancer that has spread from another site)—requires a distinctive and complex approach that integrates limb preservation, radical tumor resection, and reconstruction, all while adhering to rigorous oncological protocols. The stakes are profoundly high: an incorrect initial diagnosis or a suboptimal biopsy technique can severely compromise the patient’s prognosis and eliminate limb salvage as a viable option. Therefore, understanding when and why a case must be immediately referred to a specialist in this field—one who possesses expertise in both complex musculoskeletal surgery and tumor biology—is the non-negotiable first step in ensuring the best chance for long-term survival and functional outcome.

The Presence of a Tumor Requires a Distinctive and Complex Approach

Treating a bone tumor is a dual challenge: eliminating the cancer while preserving the maximum possible function of the limb. The presence of a tumor requires a distinctive and complex approach that moves far beyond the standard surgical techniques used for trauma or degenerative disease. Orthopedic oncology demands meticulous pre-operative planning, utilizing advanced imaging techniques like MRI and PET scans to precisely map the tumor’s margins and its relationship to vital neurovascular structures. The surgical goal is a wide margin resection, meaning the entire tumor must be removed in one piece, encased in a layer of healthy, non-cancerous tissue. This radical approach is immediately followed by a complex reconstructive phase, often involving the use of specialized tumor prostheses, allografts (cadaver bone), or a patient’s own tissue, to restore skeletal stability and muscle attachment, thereby mitigating the functional disability associated with extensive bone removal.

An Incorrect Initial Diagnosis or a Suboptimal Biopsy Technique Can Severely Compromise the Patient’s Prognosis

The margin for error in the initial stages of tumor diagnosis is virtually non-existent. An incorrect initial diagnosis or a suboptimal biopsy technique can severely compromise the patient’s prognosis and even preclude the possibility of limb salvage. The biopsy, the procedure to obtain tissue for definitive pathological diagnosis, must be planned and executed by the orthopedic oncologist who will eventually perform the definitive surgery. An improperly placed incision or a path of tissue penetration that crosses joint spaces or neurovascular bundles can contaminate surrounding tissue, turning an otherwise containable tumor into a widespread threat. This contamination necessitates a more extensive removal of tissue during the final resection, often leading to amputation where a limb-salvage procedure would have otherwise been possible. The adage is true: the first biopsy is the most critical intervention a patient receives.

The Most Common Sign Is Persistent Pain Unrelated to Activity

While many musculoskeletal issues cause pain, the characteristics of tumor-related pain are often distinct and serve as crucial red flags. The most common sign is persistent pain unrelated to activity, particularly pain that is worse at night and is not effectively alleviated by standard rest, over-the-counter pain relievers, or anti-inflammatory medications. Unlike mechanical pain from arthritis or a tendon injury, which is usually worse during motion and better with rest, tumor pain often persists during quiet repose because of the internal pressure exerted by the growing mass within the rigid bone compartment. When a patient presents with this non-mechanical pain profile, especially if it is accompanied by a palpable mass or unexplained swelling, immediate, high-quality diagnostic imaging is mandatory to rule out a neoplastic process.

Staging Is Essential for Determining the Appropriate Sequence of Therapy

Once a definitive biopsy confirms the presence of malignancy, the next step is a comprehensive evaluation of the disease’s extent. Staging is essential for determining the appropriate sequence of therapy, as the approach for a localized tumor is radically different from one that has already metastasized. Staging involves the use of whole-body imaging (usually PET or bone scans) and chest CT scans to check for spread to the lungs—the most common site of metastasis for sarcomas. The determined stage guides the entire treatment plan, dictating whether the patient requires neoadjuvant chemotherapy (chemo given before surgery to shrink the tumor and kill micrometastases) or whether surgery should proceed immediately. This interdisciplinary staging process, involving the orthopedic oncologist, medical oncologist, and radiologist, dictates the patient’s long-term fate.

Limb Preservation Does Not Equate to Functional Restoration

Modern orthopedic oncology has made remarkable strides in limb preservation, yet a common patient misconception persists. Limb preservation does not equate to functional restoration without extensive rehabilitation. A limb-salvage procedure, which may replace a large segment of bone with a custom-made metal prosthesis or an allograft, saves the extremity but fundamentally alters its biomechanics. The patient must undergo a rigorous, months-long regimen of physical and occupational therapy to adapt to the reconstructed limb, relearn movement patterns, and maximize strength and range of motion around the prosthetic joint or bone segment. Managing patient expectations—emphasizing that the goal is the best possible functional outcome, which may still involve some degree of permanent disability—is a vital part of the orthopedic oncologist’s long-term responsibility.

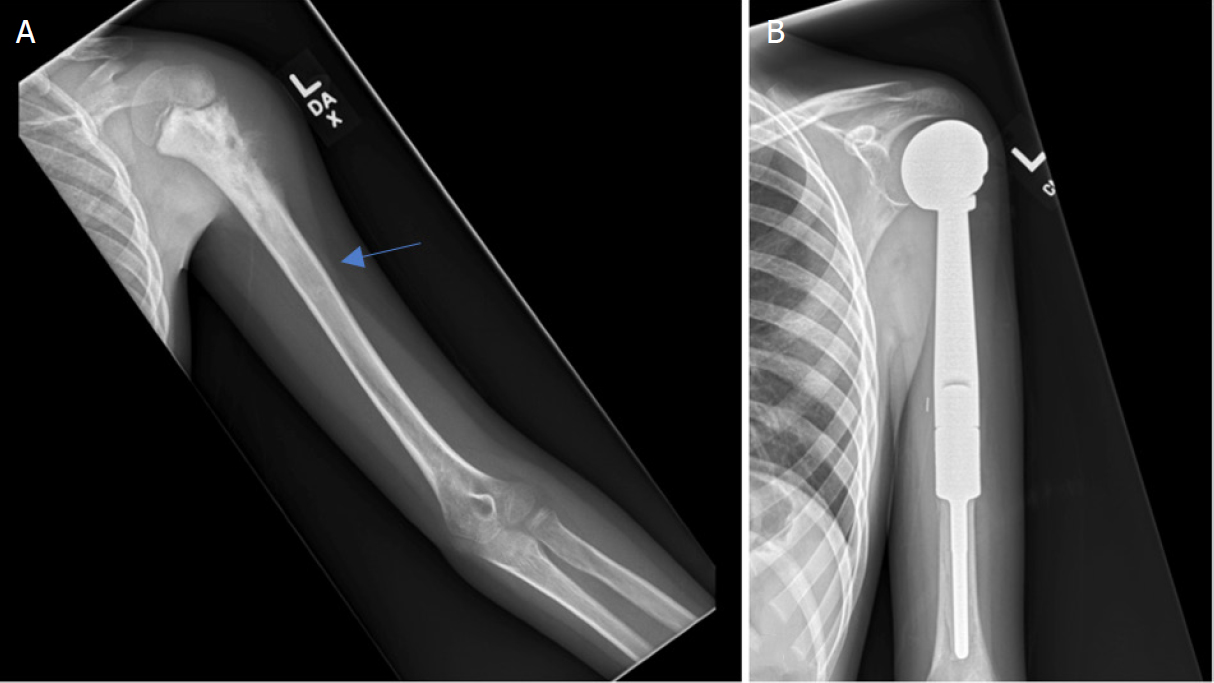

The Management of Metastatic Disease is Often Palliative

While primary bone cancers are the focus of curative treatment, the orthopedic oncologist also plays a critical role in managing patients whose cancer has spread from elsewhere in the body (e.g., breast, lung, prostate). The management of metastatic disease is often palliative, aimed at relieving pain, preventing imminent or pathological fractures, and maintaining the patient’s mobility and quality of life. Metastatic lesions frequently weaken the bone structure, creating a high risk of fracture from minimal trauma. The orthopedic intervention here is often prophylactic (preventative), involving stabilizing the threatened bone with rods, plates, or cement, or resecting the painful lesion. These procedures, while not curative, are profoundly important in allowing the patient to remain independent and comfortable during their systemic cancer treatment.

Pediatric Bone Sarcomas Present Unique Challenges Due to Skeletal Growth

The treatment of bone tumors in children, such as Osteosarcoma and Ewing Sarcoma, introduces a layer of complexity absent in adults. Pediatric bone sarcomas present unique challenges due to skeletal growth, as the tumor is often located near or involves the physis (growth plate). Removal of the tumor must eliminate the malignancy without causing severe, long-term limb length discrepancies or joint deformities. Orthopedic oncologists often use expandable or growing prostheses that can be magnetically lengthened non-invasively as the child grows, thereby accommodating their skeletal development and delaying the need for further major surgery. This specialized consideration for a growing skeleton is a hallmark of dedicated pediatric orthopedic oncology care.

The Oncological Principles Must Never Be Compromised for Function

In the delicate balance between cancer clearance and functional preservation, the priorities must remain absolute. The oncological principles must never be compromised for function—removing every single cancer cell takes precedence over every other goal. If achieving a clear, wide surgical margin requires amputation, that decision is made without hesitation because any residual cancer will jeopardize the patient’s life. The successful orthopedic oncologist is one who can seamlessly integrate the radical demands of tumor surgery with the intricate planning of reconstruction, ensuring that the primary goal of cancer control is achieved first, allowing the subsequent focus to shift entirely and safely to the complex task of functional restoration.

Multidisciplinary Teamwork is the Standard of Care

Given the multifaceted nature of bone cancer treatment, no single practitioner operates in isolation. Multidisciplinary teamwork is the standard of care in orthopedic oncology. The patient’s journey is managed by an integrated team that typically includes the Orthopedic Oncologist (for surgery and reconstruction), the Medical Oncologist (for chemotherapy and targeted therapy), the Radiation Oncologist (for localized radiation), and specialized Pathologists and Radiologists. Regular tumor board meetings where these experts discuss the case collectively ensure that the patient receives a synchronized, evidence-based, and complete sequence of care, optimizing timing, modality selection, and long-term surveillance protocols.

Long-Term Surveillance Is Mandatory for Early Detection of Recurrence

Even years after successful surgery, the threat of cancer recurrence or metastasis remains. Long-term surveillance is mandatory for early detection of recurrence and is a non-negotiable part of the orthopedic oncology patient’s life. This surveillance typically involves routine physical examinations, serial imaging of the surgical site and the chest (CT or X-ray), and clinical follow-up that can span decades. Early detection of a local recurrence or a new metastasis drastically improves the chances of successful second-line treatment, whether it involves revision surgery, focused radiation, or systemic therapy. This commitment to continuous, rigorous monitoring underscores the lifelong partnership between the patient and their specialized orthopedic team.